High blood pressure or hypertension is the leading cause of death from heart disease and stroke in women, and it is considered one of the most neglected because many women remain undiagnosed. Among those who are treated for hypertension, only a small number achieve optimal levels.

When you say that your “blood pressure is normal,” what is your (or your doctor’s) definition of normal?

A blood pressure of 120/80 mm of mercury is considered normal, but is it too high for women?

Hypertension is called the “silent killer” because you may have high blood pressure and not know it until the disease has progressed or you had your blood pressure checked. Hypertension does not mean “high tension” in your life. It is a measure of the pressure of blood in your blood vessels.

Blood pressure is measured as two numbers; the upper number is called the systolic blood pressure (SBP), and the lower is diastolic blood pressure (DBP).

What is normal blood pressure for women?

Normal levels in medicine are decided based on the level at which people are not at risk of dying or falling ill. A “normal” blood pressure would be systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels with the least or absent risk for heart disease and stroke (Cardiovascular Disease CVD). Uncontrolled hypertension leads to numerous complications like heart attack, stroke, heart failure, kidney failure, sexual dysfunction and dementia.

For many years a systolic blood pressure level of 120 was considered normal for both men and women. Based on the findings from the landmark SPRINT trial, guideline-recommended blood pressure thresholds were lowered to 120/80 mm Hg. But even this landmark trial had only 35% of women, and the findings were not differentiated based on sex.

However, a paper published in the journal Circulation in 2021 titled Sex Differences in Blood Pressure Associations With Cardiovascular Outcomes gives us pause for thought.

What did this study find?

There was a time when women were not represented adequately in studies. Experts thought that women were “like small men,” and therefore what worked for men was just as good for women! However, things have changed to some extent. Medical studies now include men and women. But when the study results are analyzed, men and women are often compared to each other instead of comparing women to women and men to men.

This study (Hongwei,2o21) looked at the systolic blood pressure (SBP)of more than 14000 women from several studies. When followed for several years, many of them developed heart disease and stroke. The study authors classified the SBP levels at which men and women developed heart disease and stroke. What they found is very significant for women with hypertension.

- SBP of 100 to 109 mm Hg compared to SBP less than 100 mm Hg was associated with heart disease and stroke in women but not in men. A similar risk in men was seen at an SBP of 130-139 mm Hg.

- The risk for heart attacks for women with SBP 110 to 119 mm Hg was comparable with the heart attack risk for men with SBP ≥160 mm Hg.

- Similarly, the heart failure risk for women with SBP 110 to 119 mm Hg was comparable with heart failure risk for men with SBP 120 to 129 mm Hg.

What about the risk of stroke?

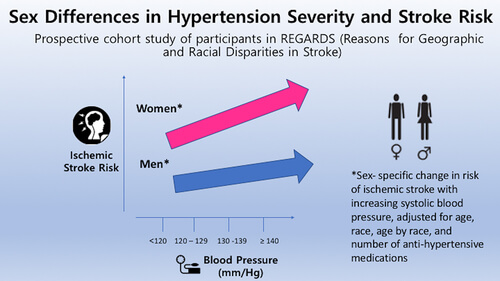

As you can see in the image below, the stroke risk was higher in women (pink arrow) than in men at the same blood pressure level.

What are the reasons for the differences in risk between men and women? It is not all about menopause.

There are several reasons for the differences. The main ones are the following:

- Sex differences in genetic risk for hypertension. Hypertension is a polygenic disease. It means several genes impact risk, with each genetic variation having a small impact, but the cumulative impact may be significant. The genetic burden may be more important in women than in men, particularly in early-onset hypertension. (Kauko 2021).

- Menopause and blood pressure.

- Different risk factors in women. PCOS and reproductive history.

- RAAS (renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system) is an important regulator of blood pressure and heart function. Men and women differ in how this system works. (Hilliard 2013)

- Immune system differences. All diseases are immune system problems. The paper by Crislip,2016 describes the differences in T-cell function and hypertension in men and women.

Menopause, hormones, different blood pressure trajectories in women.

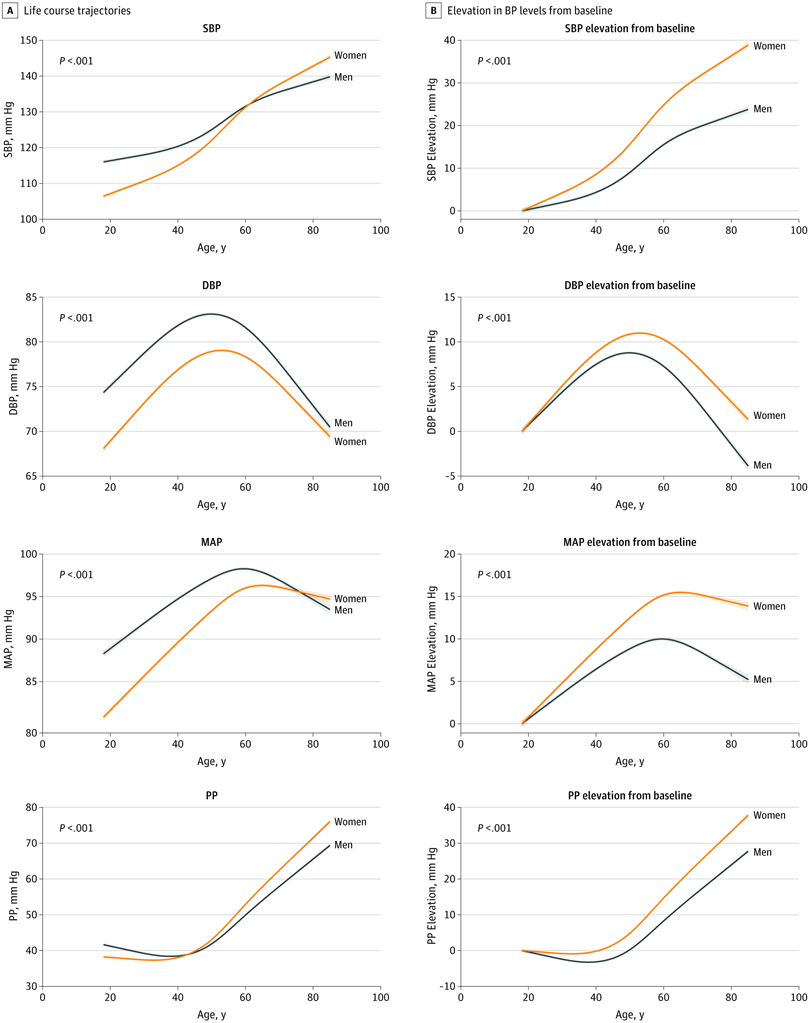

Blood pressure trajectories over the life course differ in men and women.

Blood pressure changes over the life course are different in men and women. In women, BP starts rising as early as the third decade and continues throughout life. Many women (and men) consider hypertension as a problem for older people, but this is not true. (Young hypertension is an important undiagnosed problem worldwide.)

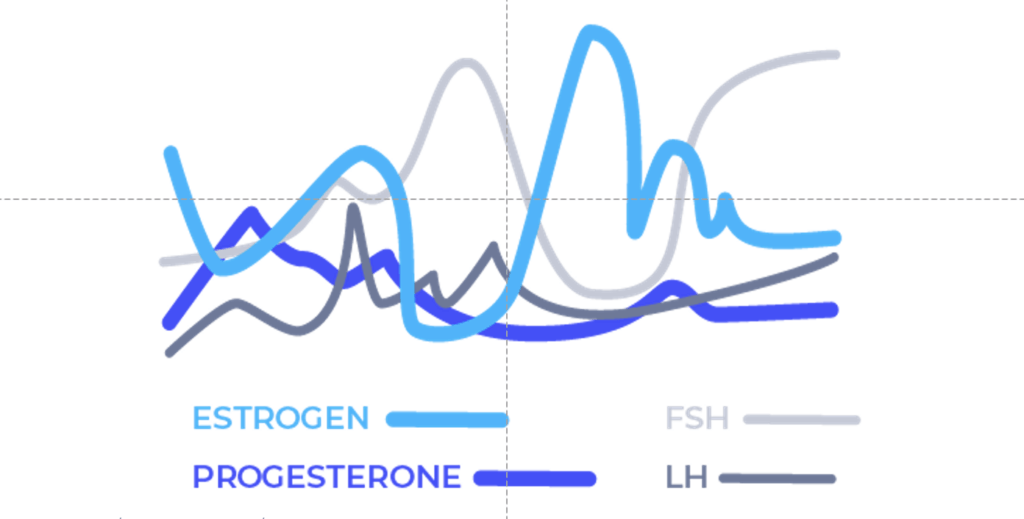

Hormonal changes during perimenopause and menopause.

Most conversations around menopause focus on “estrogen deprivation.” But the menopausal transition is often a time of hormonal chaos and not just a problem of low estrogen, as shown in the image below:

sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG), testosterone and blood pressure

SHBG is a protein made by the liver. It binds to three sex hormones found in both men and women. These hormones are estrogen, dihydrotestosterone (DHT), and testosterone. Hormones act through the free or unbound part. Therefore, if SHBG is low, it would mean that there are more free hormones available to act on tissues. This would seem like a good thing until we look at testosterone levels in women and hypertension.

A study from Sweden showed that in women lower levels of SHBG were associated with hypertension. (Daka 2013).

A study called Association of free androgen index and sex hormone–binding globulin and left ventricular hypertrophy in postmenopausal hypertensive women found that LVH (left ventricular hypertrophy is the enlargement of the left chamber of the heart as a result of high BP and is commoner in women) was higher in women with higher free androgen index and lower SHBG. The free androgen index is a measure of free testosterone in the blood.

Basically, in postmenopausal women with hypertension, low SHBG= more testosterone = worse heart function.

menopause and blood pressure

For many years experts believed that premenopausal women were protected against heart disease and stroke, but recent studies have shown that that is not entirely true.

Blood pressure trajectories change in the third decade of a woman’s life (Remember, blood pressure affects heart disease and stroke).

Even amongst premenopausal women PCOS, pregnancy diabetes, pre-eclampsia, infertility and adverse pregnancy outcomes raise the risk for hypertension.

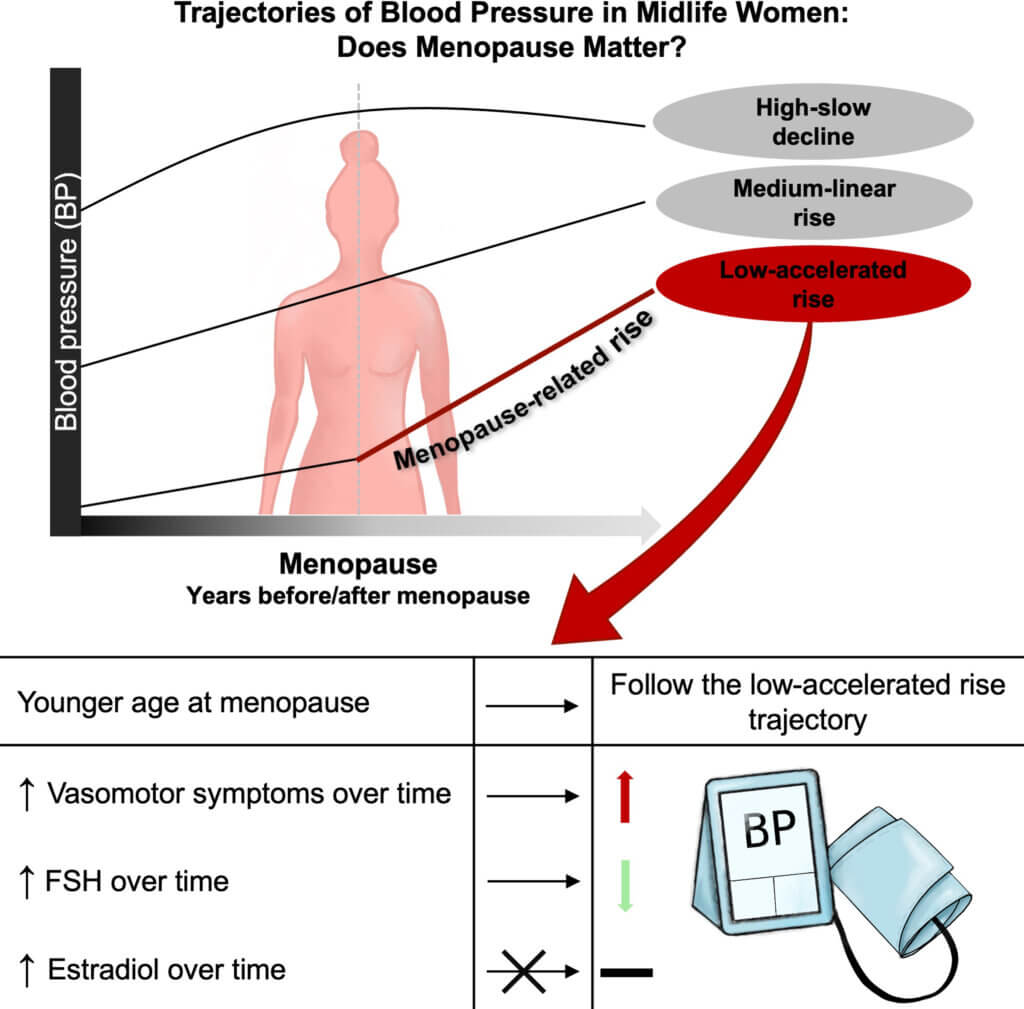

All women are not the same. A study aptly named Blood Pressure Trajectories Through the Menopause Transition: Different Paths, Same Journey shows that there are different blood pressure trajectories in women. (Image below). Regardless of the path, the actual blood pressure numbers matter!

Younger age at menopause, whether natural or as a result of a hysterectomy, increase the risk of heart disease, stroke and dementia.

Will hormone therapy lower blood pressure? The route of administration and type of hormones matter.

Hormone therapy received bad press when the initial reports of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study came out in 2003. That bad press and incorrect information still persist among doctors and people in the community. It is a great disservice to women when their doctors and well-meaning friends still tell them that hormone therapy will kill them from heart disease and breast cancer.

The hormones used in the WHI study were oral estrogens made from pregnant mare’s urine and medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA). The hormone therapy recommended today is 17 beta-estradiol on the skin and oral micronized progesterone; both of these are structurally identical to what our bodies make. Oral estrogens are extremely harmful to heart health; they increase inflammation and adversely affect lipids. MPA is a progestin, NOT progesterone. It increases breast cancer risk and raises blood pressure.

In a study done 24 years ago (Seely 1999) women were given transdermal estradiol and intravaginal progesterone in doses to mimic the premenopausal state. Blood pressure was measured using a 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure test (the preferred method).

What did they find? On transdermal estradiol and intravaginal progesterone, there was a significant fall in blood pressure. Night-time BP fall is extremely significant for reducing long-term risks, particularly in women.

What does all this information mean to you?

BOTTOM LINE

- When it comes to your blood pressure, the lower, the better, but achieving lower blood pressure levels using additional antihypertensive medications may not be the best way. Medications have side effects. Some medications may lower blood pressure but do not improve the underlying problem. We do not have women-specific blood pressure targets in hypertension guidelines yet. But hopefully, more studies will change this.

- Young women, particularly those with PCOS, adverse pregnancy outcomes, infertility, pregnancy diabetes and pregnancy hypertension, are at high risk for high blood pressure, heart disease, stroke and dementia.

- Hypertension is not a problem for only older women. Young hypertension is a growing, underdiagnosed issue worldwide.

- It is very important to check your blood pressure at home and with a 24-hour ambulatory BP device. Soon, wearables that measure BP continuously will be available worldwide. One device called Aktiia is already available in Europe.

- I have outlined some natural ways of lowering blood pressure in this article.

References

- Ji, Hongwei, et al. “Sex differences in blood pressure associations with cardiovascular outcomes.” Circulation 143.7 (2021): 761-763.

- Madsen, Tracy E., et al. “Sex differences in hypertension and stroke risk in the REGARDS study: a longitudinal cohort study.” Hypertension 74.4 (2019): 749-755.

- SPRINT Research Group. “A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control.” New England Journal of Medicine 373.22 (2015): 2103-2116.

- Kauko, Anni, et al. “Sex differences in genetic risk for hypertension.” Hypertension 78.4 (2021): 1153-1155.

- Crislip, G. Ryan, and Jennifer C. Sullivan. “T-cell involvement in sex differences in blood pressure control.” Clinical Science 130.10 (2016): 773-783.

- Ji, Hongwei, et al. “Sex differences in blood pressure trajectories over the life course.” JAMA cardiology 5.3 (2020): 255-262.

- Santoro, N. A. N. E. T. T. E., et al. “Characterization of reproductive hormonal dynamics in the perimenopause.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 81.4 (1996): 1495-1501.

- Daka, Bledar, et al. “Low sex hormone-binding globulin is associated with hypertension: a cross-sectional study in a Swedish population.” BMC Cardiovascular Disorders 13 (2013): 1-8.

- Jianshu, Chen, et al. “Association of free androgen index and sex hormone–binding globulin and left ventricular hypertrophy in postmenopausal hypertensive women.” The Journal of Clinical Hypertension 23.7 (2021): 1413-1419.

- Samargandy, Saad, et al. “Trajectories of blood pressure in midlife women: does menopause matter?.” Circulation Research 130.3 (2022): 312-322.

- Seely, Ellen W., et al. “Estradiol with or without progesterone and ambulatory blood pressure in postmenopausal women.” Hypertension 33.5 (1999): 1190-1194.

- Hilliard, Lucinda M., et al. “The “his and hers” of the renin-angiotensin system.” Current hypertension reports 15 (2013): 71-79.